Why Drug Development Slowed Down (And What Can Be Done About It) - Part 1

Part 1: When Drug Development Moved Fast and Changed the World

Much has been said about how lengthy and costly it is to run clinical trials. Why it’s so bad. Why someone should fix it. It’s been said so often, it no longer matters. It got boring. I am bored by the phrase “It takes 12 years & $2.2B to bring a drug to the market.”

Much more exciting is to understand how we got here and how we can get out of it.

Over the next few months, I’ll take you on a journey from 1906 to 2035.

We’ll trace how drugs once reached patients in months, how regulation and inertia dragged us into stagnation—and how we can undo the damage.

When I started researching this series, I believed we could shave 4–5 years off today’s timelines. It’s why I founded Yendou.

Now I’m convinced we can bring drug development down to 18 months—total.

The next 7 issues will show us why. And how we can do it.

And by “we,” I mean you and I.

Let’s begin.

Part one of my seven-part series investigating R&D productivity from 1906 to today—and into the future.

Subscribe to get access to these posts, and every post.

Is it regulations? Process? Or access to patients? What really slows down drug development?

I’ve always been skeptical of the “access to patients” argument for why clinical trials stall. People are eager to test therapies that promise real benefits; such as a compounding return on their health. If a trial can’t recruit, it’s because the trial itself lacks appeal.

In a free market, products fail for one reason: no demand.

So, why isn’t there demand for health?

Colleagues I respect often point to “regulations!” This idea challenges my instincts.

Admitting regulation is the bottleneck feels like conceding that the problem is too vast to fix in my lifetime, and I’m driven to solve drug development’s delays now. That’s why I founded Yendou right! To tackle what our industry can control, like the 30%+ of trial timelines lost to inefficiencies we call “white space.”

But what about factors beyond our control? Could regulation truly be slowing us down?

Research suggests it might. For instance, studies show that unexpected FDA rejections can lead companies to abandon four to six drug projects within months, wary of tougher scrutiny. I’m not ready to fully embrace this view, but I’m stepping out of my comfort zone of denial to explore it.

My goal: understand regulation’s impact on trial timelines by examining an era when drugs moved from lab to patient at lightning speed.

This won’t be exhaustive. Unraveling how regulations and operations intertwine will take time. But let’s start at the beginning, so when the world first noticed drug development’s decline. Before that, no one realized how fast things were moving, until they stopped.

In 2012, Jack Scannell coined “Eroom’s Law”, the inverse of Moore’s Law, which showed that the number of new drugs approved per inflation-adjusted billion dollars has halved every nine years since 1950, despite rising R&D budgets and increasingly sophisticated tools. Whereas in 1950 there were 10 to 20 new drugs per billion dollars, by 2010 this had fallen to fewer than one: a staggering 80-fold drop in efficiency.

This is odd. Then scientific knowledge grows daily, and research tools are more powerful than ever. Yet trial speeds, success rates, and public health gains lag. Life expectancy improvements have decelerated, and in some countries, reversed. Each new drug demands more time, money, and effort than the last.

Why?

To test regulation’s role, we must revisit the era before it tightened its grip: the early 20th century, when insulin, penicillin, and vaccines transformed medicine in years, not decades. Let’s map the regulatory landscape and the productivity it enabled.

A- Historical Trends in R&D Regulations (- 1950)

To understand why drug development once moved so quickly, we need to examine the rules that governed it. The process didn’t simply lose momentum. It was actively slowed by the rise of a regulatory state, shifting from a system rooted in physician autonomy and public trust to one increasingly defined by control.

1. Pre-Regulation Era (Before 1906)

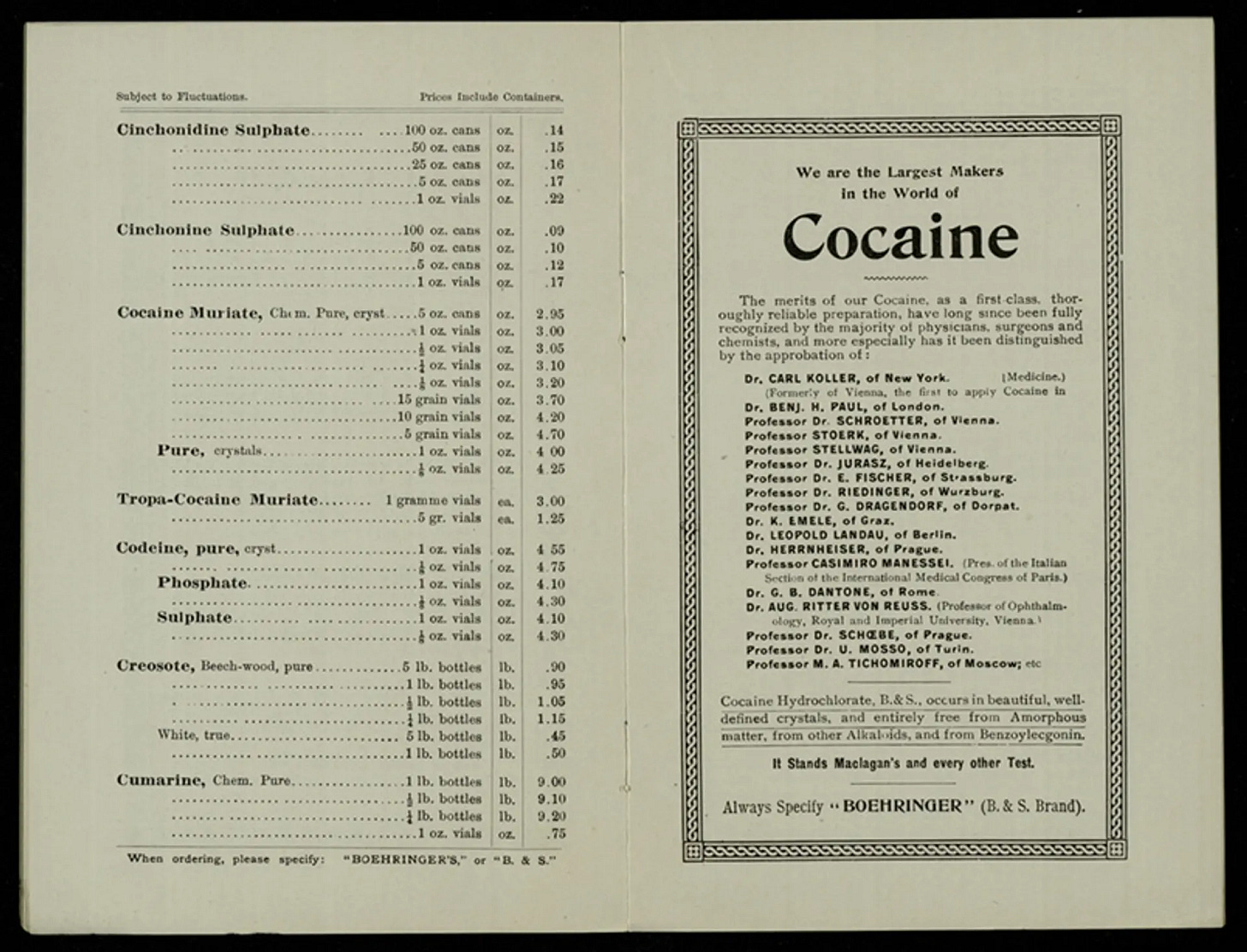

Before 1906, medicine was a wild west. “Miracle cures” laced with morphine, cocaine, or mercury flooded the market, with no disclosure required. Cocaine toothache drops were sold for children. Heroin was used as a cough suppressant. Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, spiked with morphine, calmed teething babies. Sometimes fatally.

These stories are horrifying, yet when studied in context, one can easily conclude that such treatments were often prescribed to relieve a horror worse than the one inflicted.

Take, for example, the story of cocaine’s rise as a medical miracle. My first reaction was, “This is insane,” but dig a little deeper and it becomes clear: at the time of cocaine toothpaste, cocaine was indeed the best pain relief medicine available.

In 2025, it is easy to forget that we live in an (almost) pain-free society. Surrounded by painkillers, we have lost all real sense of what it meant to live in a world where pain was a constant and crippling force, limiting not only human performance, but often the very ability to live.

The discovery of cocaine’s pain-relieving properties was, in fact, a medical marvel. While Carl Koller and Freud were experimenting with it, Koller noticed his tongue going numb and just like that, the world’s first local anaesthetic was born.

Chambers’s Journal called cocaine “a wonder of the age”. They wrote: “Cocaine has flashed like a meteor before the eyes of the medical world, but, unlike a meteor, its impressions have proved to be enduring.”

Anyone who has suffered tooth pain can imagine what it must have been like to endure such agony in a world without dentists or painkillers.

The lesson is simple: everything sounds insane when stripped of its context.

Below: a Boehringer advertisement proudly showcasing their product: Cocaine!

And yet, it is fair to summarise the spirit of the era by saying that medicine and poison were barely distinguishable.

2. The Birth of Oversight (1906–1938)

Regulation began not with drugs, but meat. In 1906, the socialist Upton Sinclair published the book The Jungle exposing cruel workers conditions in meat packaging factories.

While he was trying to hit the public’s heart for immigrants workers in the US, he hit the public’s stomach. The meatpacking conditions described in the book unleashed public fury. Reports of children dying from tainted medicines added pressure. And that was the birth of the FDA era.

Congress passed the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906, the first federal attempt to regulate medicines.

Required accurate ingredient labeling to curb deceptive marketing.

Created the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), then a bureau in the Department of Agriculture.

Lacked authority to enforce safety, leaving the FDA toothless.

The Act was a step, but dangerous drugs still reached shelves.

3. Safety and Early Efficacy Oversight (1938–1961)

A pharmaceutical tragedy changed everything. In 1937, a Tennessee company marketed Elixir Sulfanilamide, a raspberry-flavored antibiotic dissolved in diethylene glycol—antifreeze’s toxic cousin. It killed 107 people, mostly children, because no law mandated safety testing. The label said “elixir.” It lied.

Congress passed the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938, making the FDA a true gatekeeper.

Companies filed New Drug Applications (NDAs) proving drugs were safe before marketing.

The FDA could block unsafe drugs, typically within a 60-day review period.

Safety evidence came from animal and early human data, but the process was reactive. Drugs proceeded if the FDA didn’t object.

Officially, the 1938 Act didn’t require efficacy proof. A drug could be ineffective, as long as it didn’t harm.

Yet you can’t give an organism power without expecting it to want more.

By the late 1940s, the FDA began pushing for greater agency in the drug development process. The shift was subtle but deliberate. An expanding interpretation of its mandate.

Dan Carpenter, in Reputation and Power (2010), documents how Erwin Nelson, then head of the FDA’s drugs division, told companies in 1949: “We want proof of safety… but we also want proof of efficacy.” This wasn’t law, but a signal.

The FDA began using “refuse to file” (RTF) practices to reject NDAs that lacked efficacy data. Thus, setting a precedent that would later be formalised. By 1956, NDAs were required to include “full reports of adequate tests” to demonstrate safety for intended use, opening the door to assessing therapeutic outcomes.

By the mid-1950s, the agency demanded raw trial data rather than summaries, and expected evaluation by qualified experts, including clinical pharmacologists. As Carpenter shows, this was not merely bureaucratic drift. It was the FDA building scientific legitimacy and asserting epistemic authority.

This is a critical point. Most narratives around regulatory history mistakenly credit thalidomide as the trigger for structural overhaul. But as Carpenter’s work makes clear, the transformation was already underway, awaiting a trigger.

Until 1962, physicians prescribed off-label without restriction, and informed consent was not yet standardised. The FDA blocked poisons but did not dictate trial design or demand formal proof of efficacy beyond what was described above. This balance of flexibility paired with a reactive gatekeeper, enabled breakthroughs like insulin, penicillin, and vaccines to reach patients rapidly. Thus, shaping the golden era of antibiotics and medical progress. Still, the FDA’s grip was already tightening, reshaping the rules of the game long before thalidomide became the cautionary tale.

B- Historical Trends in R&D Productivity

Mid-20th-century drug development was remarkably efficient, producing insulin, penicillin, and vaccines at low cost compared to today. Data from the era shows why. In the early 1950s, FDA approvals (if existent) took a median of under six months, with 25% of drugs approved in just a few months. New chemical entities (NCEs) peaked in the late 1950s at around 50 per year, reflecting robust innovation.

This contrasts starkly* with modern inefficiencies. Eroom’s Law shows that from 1950 to 2010, drugs approved per inflation-adjusted billion dollars fell from 10–20 to under one. An 80-fold decline. By 1960, NCE approvals began dropping, a trend some link to increasing regulatory stringency, We will discuss the next era of regulations in the next issue.

Below are timelines for insulin and penicillin, illustrating their rapid paths In the pre-efficacy regulation era:

Insulin Development Timeline

Penicillin Development Timeline

This efficiency of drugs from lab to market in 2–3 years stands in contrast to today’s decade-long timelines, raising questions about what changed.

1- The Insulin Story: A Rescue Mission, Not a Trial

Insulin was discovered on July 27, 1921, by Frederick Banting and Charles Best in a basement lab at the University of Toronto. Armed with few dogs, and one clear idea: that diabetes could be controlled by isolating secretions from the pancreas.

Between that discovery and the first human injection just six months later, a series of high-stakes experiments unfolded. The early work was messy—most dogs died. But in August 1921, one diabetic dog, Marjorie, was kept alive for 70 days on pancreatic extract alone. The result wasn’t elegant. But it was a signal.

By autumn, they brought in John Macleod, who had given them lab space, and biochemist James Collip, who worked relentlessly to purify the extract through December 1921.

Then came Leonard Thompson—a 14-year-old boy, weighing 29 kilograms, dying of Type 1 diabetes at Toronto General Hospital.

On 11 January 1922, they gave him his first injection. It failed. The extract triggered a severe allergic reaction. Collip refined it. Twelve days later, they tried again. This time, it worked. Leonard’s blood sugar dropped. He sat up in bed, asked for food, and began to recover.

No placebo. No randomisation. No multi-arm trial. Just a dying child and a breakthrough.

By March, six more children received insulin under compassionate use, including Elizabeth Hughes, the daughter of the U.S. Secretary of State. She lived another 58 years.

But demand soon outpaced what the Toronto team could deliver.

In May 1922, they partnered with Eli Lilly to scale production. Chemist George Walden developed a more stable method using alcohol fractionation. By October, hospitals began receiving insulin. By January 1923, full-scale production was underway. By year’s end, insulin was being delivered across North America and Europe.

Banting and Macleod received the Nobel Prize—less than 24 months after their first dog experiment.

That’s the speed we once moved at—when the signal was clear, and the regulatory system didn’t yet demand an elaborate process leading to years of trials.

2- The Penicillin Story: Wartime Urgency Meets Relentless Coordination

If insulin was a rescue mission, penicillin was a wartime moonshot.

What’s Penicillin? Penicillin is an antibiotic primarily used to treat infections caused by gram-positive bacteria. It works by inhibiting bacterial cell wall synthesis, which causes the bacteria to rupture and die.

At the time of penicillin’s discovery in 1928, approximately 300,000 Americans died from bacterial illnesses, accounting for about 22% of all deaths that year, making bacterial infections a leading cause of mortality.

By 1952, penicillin dramatically reduced deaths from these infections to only about 6% of all deaths that year.

Discovered almost accidentally in September 1928 by Alexander Fleming, penicillin didn’t reach patients for over a decade. Fleming’s original observation of the mold killing bacteria was compelling but crude crude, lacking purification tools. In 1939, Oxford scientists Howard Florey, Ernst Chain, and Norman Heatley resumed work as war loomed.

Preclinical Studies: On May 25, 1940, Howard Florey and his team at the University of Oxford conducted a pivotal experiment to test penicillin’s efficacy. Eight mice were infected with a lethal dose of Streptococcus bacteria. Four of these mice were then treated with penicillin. By the next morning, all untreated mice had died, while the treated ones survived. This experiment provided compelling evidence of penicillin’s potential as a therapeutic agent.

Following this success, the team faced the challenge of producing sufficient quantities of penicillin for human trials. Penicillin was notoriously difficult to purify and produce in large amounts. The team resorted to using various containers like bedpans and milk churns to cultivate the mold. Despite these efforts, yields remained low, necessitating further innovation in production methods.

First Human Trial: From there, urgency escalated fast. The first human recipient of penicillin was Albert Alexander, a 43-year-old police constable. In December 1940, Alexander suffered a severe facial infection, possibly from a rose thorn scratch or injuries sustained during a bombing raid. His condition deteriorated despite conventional treatments, leading the Oxford team to consider him for penicillin therapy.

On February 12, 1941, Alexander was administered 160 mg of penicillin intravenously. Remarkably, his condition improved within 24 hours. However, the limited supply of penicillin meant that the treatment could not be sustained. The team even attempted to extract penicillin from Alexander’s urine for reuse, but supplies eventually ran out. Despite their efforts, Alexander died on March 15, 1941. But the signal was undeniable.

The race to scale began.

In June 1941, Florey sought U.S. partners in Peoria, Illinois. Scientists at Pfizer, Merck, and Squibb optimized deep-tank fermentation. By 1943, production scaled; by D-Day 1944, penicillin treated every wounded Allied soldier. Fleming, Florey, and Chain won the Nobel Prize in 1945.

No placebo. No randomisation. No multi-arm trial. Just a world on fire and aligned stakeholders, academia, government, industry. All driven to save lives.

Since the Approval of Penicillin in 1944…

After 1944, a “golden age of antibiotics” unfolded. Drugs reached patients in under two years, driven by urgent medical need and a regulatory system that was rigorous, yet flexible. The FDA’s scrutiny evolved from focusing on safety to, by the late 1940s, expecting evidence of efficacy. This ensured quality without yet stifling speed.

The era’s ethos, namely cure above all, fuelled a Moore’s Law-like trajectory for medicine, outpacing even early computing. But as regulations tightened, timelines stretched, and the stage was set for today’s delays.

What Did Regulation Look Like Then?

Between 1938 and 1961, innovation was largely entrusted to physicians and scientists, while the FDA operated as a reactive, and increasingly proactive, gatekeeper. Under the 1938 Act, companies submitted NDAs with safety data, usually from animal and early human tests. By the late 1940s, the FDA began rejecting applications lacking clear therapeutic benefit.

Trials were informal, single-arm, physician-led. There were no INDs, no randomisation, no Phase 1/2/3. Off-label prescribing was common. Informed consent was not standardised.

Advertising faced light oversight, though the FDA began challenging unproven claims in the 1950s. The system enabled fast market entry for antibiotics, antihistamines, and hormones, transforming care with astonishing speed.

It was this balance of speed, trust, and soft rigor, that drove breakthroughs. But in 1962, the rules changed.

Conclusion

The early 20th century shows what’s possible when urgency and flexibility align. Insulin and penicillin reached patients in under three years. Not despite regulation, but because the system prioritised safety, delegated efficacy to clinicians, and avoided rigid trial structures.

Yet even then, the FDA’s authority was expanding. The groundwork for today’s decade-long timelines was already being laid.

As we confront Eroom’s Law and increasingly complex pipelines, understanding this era is more than historical interest. It’s design insight. In the next issue, we’ll explore how the thalidomide tragedy reshaped drug development forever and what was gained, and lost, in the process.

This was Trials & Triumphs - On the relentless pursuit of progress at the intersection of scientific breakthroughs and operational reality & I am Zina Sarif, Founder CEO of Yendou, breaking Eroom’s law.

Enjoyed the read? Share it. Spark new thinking.

Sincerely,

Zina

Capitalism can’t stomach subtlety.

It craves pills. Products. Apps. Predictable returns.

But breath?

Breath doesn’t play like that.

https://thehiddenclinic.substack.com/p/you-cant-patent-breath